Department of Basic-level Governance, Ministry of Civil Affairs (MCA), PRC

Translated by Ying Shang; Proofread by Matt Hale

|

Background Chinese Villager Committee (VC) elections began to take shape during the early 1980s. The 1982 Constitution stipulated: "Neighborhood Committees and VCs are autonomous institutions. The chairs and vice chairs of these institutions are elected by residents within the relevant residential districts." We can divide the development of VC elections into three stages since then. From 1982 through 1987, the Central government dissolved the commune system nationwide and established about 940,000 VCs. Although previous commune leaders typically simply changed production brigades to VCs without conducting any elections, some villages in Henan, Fujian, Jilin and Hunan Provinces held elections for new leaders to serve as VC members. At that time, the lack of relevant official regulation left actual electoral procedures informal and improvised. In 1987, the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPC) passed the Provisional Organic Law for Villager Committees (the Organic Law), which included regulations on electoral procedures. During this second stage of development, the MCA attempted to implement the Organic Law and gradually standardize elections. The MCA first organized elections in pilot villages, then during the next ten years extended its work to broader regions, combining official regulations with model village experience as a guide. It promoted activites to guarantee democratic rights, such as campaign speeches, secrect ballot booths and direct nomination by villagers. After many villages had elected three or four rounds of VCs, the Standing Committee of the NPC passed a revision of the Organic Law on November 4, 1998, which stipulated multiple candidates, villager nomination, secret ballot, and on the spot ballot count announcement. 20 province-level regions began the third stage of election development by organizing a new round of elections according the revised Organic Law . Guangdong Province also finally abolished most of the province's appointed village-level offices and instituted VC elections. By the end of 1998, 832.9 thousand democratically elected VCs had been established with over 3 million VC members. We can outline the improvement of elections along these lines: 1. Supplementation through Provincial Measures 2. Tendency toward a unified time of election 3. Multiple election modes 4. Growing participation 5. Growing intensity of election campaigns A proper evaluation of election procedure is critical to the further improvement of election quality. The current methods used in evalution are monitoring (on-the-spot observation of elections with attention to implementation of rules), investigation (review of election archives and interviews), and having local officials report data to higher levels of the government. For this last method, Village Election Committee (VEC) members fill out report forms to submit to the township-level Bureau of Civil Affairs (BCA) after each election, and the reports are then transmitted up to the MCA (national) level. The first two methods are more practical and accurate, but limited by their specific nature. The last method is more frequently used, but has obvious weak points. It is less efficient because of document travel time. Report submission is also often less accurate because township and county levels may alter statistics before the reports reach the national level. This method of data collection, furthermore, suffers from variation of statistical presentation, despite MCA distribution of standaradized statistical forms. The reports, finally, are often overelaborate and convoluted. MCA's 1995 report form, for instance, contained 10 major items and 42 sub-items, the Henan DCA's form had 8 items and 63 sub-items, and the 1998 form for Lishu County, Jilin had 15 items and 133 sub-items. The MCA has gone to great lengths to improve the quality of statistics, including accuracy requirements for local governments and random spot-checks. It planned to establish a nationwide electronic data collection system with state-of-the-art technology, but the initial 1996 agreement with the Canadian Department of Planning and Development finally failed. While the MCA has since developed its own system using the internet, obstacles remain. Namely, most county-level BCAs still lack computers or consistent internet access, the software is not specialized for the task of such data collection, and local officials still undervalue the data collection itself, putting more emphasis on the actual election turnout. The Carter Center, established in 1982 for the purpose of promoting world peace and development, has extensive election monitoring experience throughout the world. The Center organized two field studies of VC elections in Fujian, Hebei, Liaoning and Hunan Provinces in March 1997 and March 1998. During these studies the Center proposed to help the MCA in establishing their nationwide data collection system. The two parties signed a memorandum of understanding on March 14, 1998, with the long-term goal of “establishing a rapid, transparent, and nationwide data collection system.” They then agreed to conduct pilot projects in two or three provinces. MCA selected nine county-level districts from the 2,857 county-level districts in China to be pilot districts: Linli, Shuangfeng, and Xiangtan Counties of Hunan Province; Huli District (of Xiamen City) and Gutian and Xianyou Counties of Fujian Province; and Huadian City and Dongfeng and Lishu Counties of Jilin Province. Selection and Background of the Pilot Counties The first and most critical step of this project was to select the pilot county-level districts. The MCA set a series of conditions for the selection process:

The nine districts named above fulfilled these conditions, among which Lishu County of Jilin Province, Linli County of Hunan Province, and Gutian County of Fujian Province were model districts. Among the nine districts, Lishu, Xianyou, and Linli Counties were typical agrarian regions, and Hudian City and Huli District of Xiamen City were more industrial. The common feature of the districts was that they had begun holding elections relatively early, and the procedures had become relatively standardized. The pilot project involved 3,267 VCs and 3,124,779 voters. Linli County lies in northwestern Hunan, with an area of 1209.58 Km2, 9,060 acres of cultivated land, and 17 townships under its administration. The first VC election was held between February 24 and the end of March of 1989, and 92.5% of eligible voters participated. 1,361 village cadres were elected, among which, 1,070 of them were incumbents, 260 were women, and 814 were CCP members. The second election was held between September and December of 1992, and 1,050 of the 1,270 elected were incumbents. The average age of the elected cadres was 39.3. The third election, which was the basis of this pilot survey, was held between October 10 and December 25 of 1995, for which the MCA awarded the county the National Model County of Village Autonomy in 1995. Linli County received this award again in 1999. Shuangfeng County lies in central Hunan, close to the provincial capital. It is also an agrarian district, spanning 1,715 Km2 with 16 townships and 800 thousand residents. The village election was one of the most important issues on the county agenda, and three terms of elections had taken place, in 1989, 1992, and 1995. The turnout rates of the first two elections are 81.5% and 75.2% respectively. The township BCA extensively publicized the elections via television, blackboards, banners, posters and other media. Shuangfeng was also recognized as a National Model County of Village Autonomy in April 1999. Xiangtan County lies in central Hunan, with 22 townships, 757 VCs, 10,672 villager groups, and 1.04 million residents. Three elections took place in 1989, 1996, and 1999, and it was recognized as a Model County in April 1999. Gutian County lies in northern Fujian, close to the provincial capital Fuzhou. It spans 2,395 Km2 and has 15 townships. Since the VCs were set up in 1984, 6 terms of elections have taken place, in 1984, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1994, and 1997. According to provincial standards, 97% of the county's VCs manage village affairs well, and 65% are ranked as "excellent." Gutian has been Model County twice, in 1995 and 1999. Huli District of Xiamen City lies on northern Xiamen Island, and was established in October 1987. It has 58.2 Km2 area, one township and one sub-district, 11 village committees, 22 neighborhood committees, and 39 thousand residents. The annual industrial production in 1996 of this district was RMB 2.48 billion, with more than RMB 100 million in revenue, and RMB 4,500 per capita income. It has held six rounds of elections and achieved Model County status in 1999. Xianyou County is a 1,300-year old district in southern Fujian, of 1,824 Km2 and 19 townships. Its elections were held in 1990, and 99% of the VCs accorded with the provincial standard. In 1994, 90% of the villages participated in the second round of Model Demonstration. Xianyou was recognized twice as the Provincial Advanced County on Village Election, and became National Model County in 1999. Lishu County lies in southwestern Jilin Province, with 409 Km2, 32 townships, and 335 VCs. Its first elections took place in December 1989, and most of the nominations occurred through the Village Party Branch, freely associated nomination (with over 10 supporters), and self-nomination. 93.5% of eligible voters participated, and 2,352 cadres were elected with an average age of 45.3. Among the elected, 336 were women, and 1,317 were party members. The second election took place between December 1991 and January 1992. The individual nomination was accepted in addition to the ways listed above. 94.3% of eligible voters participated, and 1,792 cadres were elected, average age 41.5, with 336 women, and 1,271 party members. The third election took place between December 1994 and January 1995. Individual voters nominated all the candidates. 95.1% of eligible voters participated and 2,083 cadres were elected, average age 39.8, with 338 women and 1,066 party members. Lishu achieved National Model County status twice, in 1995 and 1999. Dongfeng County lies in southern Jilin, with 2,487 Km2, 23 townships, and 229 VCs. The first election took place in March 1989, and the Village Party Branch nominated all the candidates. 98.6% of those eligible voted, and 1,351 cadres were elected, with 222 women. The second election took place in August 1992, where villager small groups and freely associated nomination were permitted in addition to party nomination. 96.1% of those eligible voted for 1,224 cadres, average age 38, with 231 women and 196 party members. The third election took place in March 1995, which employed five methods of nomination: party nomination, villager small group nomination, freely associated nomination, self-nomination, and individual nomination. 97% of those eligible voted for 1,046 cadres, among which 238 were women, and 413 were party members. Dongfeng became a Model County in 1999. Huadian City lies in central Jilin Province, with 6,250 Km2, 16 townships, and 179 VCs. Its first election took place in November 1989 with three methods of nomination: party, villager small group, and freely associated nomination. 88% of those eligible voted for 1,084 cadres, with 222 party members. During the second election, in November 1992, the candidates were mainly nominated by villager small groups and free associations. 90% of eligible voters elected 2,158 cadres, among which 208 were party members. During the third election, between October and November 1995, nominations occurred mainly through villager small groups, free associations, and individuals. 95% of eligible voters elected 895 cadres. Huadian became a Model City in 1999. Process of Data Collection and Data Analysis Crucial election data included indications of the standardization of elections and the aspects of elections in need of improvement, on the one hand, and the election results themselves, which strengthen faith in rural democracy when more qualified cadres are voted into office. For these two sets of data we designed two forms, the "Assessment of the Village Electoral Process" and the "Report of Village Election Results". The first form is to evaluate the electoral procedure, including methods of voting, nomination, selection of candidates, proxy vote, count and announcement of the result, posting vote, roving ballot boxes, and the construction of VECs. The second form shows election results, including name, position, sex, age, nationality, political status, and education of the elected cadres. After collecting data from Fujian, Hunan, and Jilin Provinces, we asked GC Information Inc. to develop software based on these two data forms. MCA printed the forms and distributed them to the pilot districts via the provincial DCAs. The pilot districts sent two forms to each village, along with county-level BCA assistants to supervise VEC chairs in filling out the forms and then collect the completed forms. County-level BCA computer personnel then entered the data into their hard drives as original data and then sent the data to the provincial BCAs, who finally sent the province-wide data to the MCA. Both county and province-level BCAs were permitted to do some rudimentary analysis on the data. The MCA finished installing computers in July 1998 and, in order to guarantee accuracy of data input, organized an operational training course in Beijing between August 31 and September 6, 1998. 22 computer operators from the nine districts attended the course and then began to work on the project, which lasted until January 1999 (five months). We attribute the extension of project time beyond that anticipated to:

The MCA completed the project successfully, however, and in less time than a non-electronic data collection would have taken. Each district required a different length of time to complete the data collection, depending on the number of villages per district. Huli District of Xiamen City in Fujian, for instance, had only 11 sub-village committees and therefore 22 forms to fill out, while Shuangfeng County of Hunan had 864 VCs and 1,728 forms (see Table 1). Table 1: Number of Villages in Each County-level District

Another factor influencing the project was the amount of attention the county-level BCAs contributed. Both township and county-level BCAs may not benefit economically from preparing these statistics, so their progress was proportional to the amount of supervision the county-level BCA undertook. The ability and experience of computer personnel was also an issue. According to our estimation, entering one form should take three to seven minutes. The total data input times per village were as follows: Gutian 2670 min, Xianyou 3040 min, Lihu 110 min, Linli 3180 min, Shuangfeng 8640 min, Xiangtan 7570 min, Lishu 3360 min, Dongfeng 2290 min, and Huadian 1790 min. At five hours per day, the longest input period was 28.8 for Shuangfeng County in Hunan Province. Poor handwriting on the original forms was also a problem. Provincial DCAs also slowed the collection of data at the national level when they undertook statistical analysis before sending on the data, although this was usually not a problem. According to the description above, two factors emerge as critical for the success of data collection: quality of the form design and validity of the data collected and reported. The forms designed in 1997 were easy to fill out and provided sufficent data, but they still need revision in the following areas:

There has been a lack of efficient verification of the validity of the data. Although generally more reliable than the traditional method, forms are still vulnerable to modification by township and county-level officials, especially when they find the data shows the problem of their elections, such as a low turnout rate. According to the data we have already received, some choices, such as “the result was not announced on the election meeting,” or “the final candidates are decided by the village party branch,” were rarely chosen. Training courses are also essential, both for BCA assistants in understanding the report forms and for computer personnel in data entry. Both provincial and county-level civil affairs departments may consider including these two training programs in their regular election offical training courses. Data Entry and Analysis The Chinese Villager Committee Information System is the first software developed specifically for grassroots elections, its main functions being data modification, date inquiry, data transfer and reception, statistics and analysis, and data printing. With the information collected, the county-level BCA can set up a database for the district, the provincial DCA can set up a data center, and the MCA can establish a national data center. This information can also serve as a reference for the later decision making. Data transfer is also an important part of the software, which allows the data to be delivered via internet, public telephone line, or disk. The main platform is clear and the operation is easy. Weak points in the software that may be improved in the upgrade include: 1. Stability of the system 2. Lack of flexibility 3. Inability to expand database 4. Lack of compatibility with other statistics software 5. Problems with printing 6. Selection of the survey questions and sample size 7. Inquiry function Data Analysis on VC Elections The data collected were not on the village elections spanned several years, from 1995 (Hunan) to 1998 (Jilin). Since the enforcement of the Organic Law varied from year to year, the standardization of the elections differed as well. Generally speaking, Hunan applied more methods and was more creative, while Fujian and Jilin were better at standardization. The data encompasses 3,267 VCs and 3.12 million villagers (see Table 2). The turnout rates per province were 93.65% in Hunan, 87.12% in Fujian, and 97.02% in Jilin. Fujian's low turnout rate is attributed to that province's restriction of voting to voting stations. Election meetings, being more convenient, disciplined and organized, resulted in higher turnout rates for the other two provinces. Table 2: Basic Data from All Nine County-level Districts

The first important procedure was to form the village election committee (VEC). Allowing villagers to select the VEC themselves may guarantee more fairness and justice in elections, as opposed to allowing a certain social power to control the VEC formation. According to our survey, 3,261 out of 3,267 villages (99.82%) organized their election committees through villager selections; township governments appointed the other six.The total number VC members elected was 19,067, with an average 5.8 members per village. 51.39% were party members (see Table 3). Table 3: Percentage of Party Members in Village Election Committees

The initial nomination of candidates was the second important procedure. Since the Organic Law did not stipulate the details of this procedure, provinces made their own regulations (All the village committee elections of the nine counties were held according to the Provisional Organic Law, and revised Organic Law was passed on November 4, 1998.). Hunan had five methods of nomination: through the free association of five to ten villagers, through villager small groups, through villager meetings, by individuals (haixuan), and self-nomination (After this election, Hunan passed the Regulation of the Village Committee Election of Hunan Province on November 28, 1996, and there are three methods of initial nomination, which are the individual nomination, the villager small group nomination, and the self-nomination.). Fujian’s regulations, passed in 1990 and revised in 1996, permitted nominations only through the free association of five villagers, while Jilin promoted the haixuan, (which originated in Lishu County of that province). Besides the villager meeting nomination, all the other methods could reflect the will the common villagers, with the haixuan as the ideal in this regard, but requiring extensive organization work. Among the three provinces, haixuan was most prevelant at 40.77%, and free association comprised 30.55%. Nomination by village party branch, once the dominant method, decreased to only 0.03% (see Table 4). Table 4: Initial Nomination Statistics for Total Data

"No Answer" indicates that this section was left blank on the original forms. These forms largely came from Lishu County of Jilin, where the nomination method failed to match any of the suggested types. According to the statistics, 58.82% of the villages in Jilin used individual nomination and 41.05% used this new method (Villagers in Lishu County voted with a blank ballot, on which they may write on anyone they want to vote for. Those who get enough votes were elected. If there were not enough votes, nomination will be made according to the vote the candidates have already had, and another vote or supplementary vote would be held again.), so the total percentage of villages that used some form of direct individual nomination reached 99.87% (Lishu had 335 villages, 45.09% of the total number of villages in Jilin). The major nomination method in Fujian was by free association (99.15%). The nominations in Hunan were more complicated; Table 5 shows the distribution in details. Table 5: Nomination Statistics for Hunan

The five choices we provided for the decision on the final candidates (primary elections) included “by village party branch," "by villager representative meeting," "by all voters," "by initial nomination votes," and "other.” The data shows that 50.87% of villages conducted primary elections through village representative assemblies, 31.47% decided by initial nomination votes, and 6.29% held general primary elections (see Table 6). 97.26% of the villages of Fujian selected final candidates by village representative assemblies, which raised the level of demand for those representatives. Haixuan combines the initiate nomination with the decision on the final candidates. These villages accounted for 41.26% in Hunan and 30.69% in Jilin. Actually, haixuan could be regarded as a primary election without formal candidates. There is no clear distinction between the “direct primary by the entire village” and “number of votes received in the nomination," and they are easily confused, so Lishu County gave up answering the question; as a result the statistics of Jilin on final candidates showed 45.16% with no answer. Table 6: Statistics on Selection of Final Candidates for Total Data

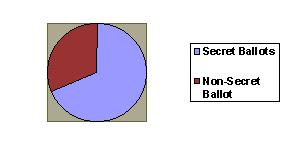

The data illustrates that both the initial nomination and the decision on final candidates were becoming more liberal, and, according to the Organic Law, these procedures are the two most sensitive and influential on the fairness and justice of village elections. We accept as a general rule that a larger number of candidates indicates a greater degree of variety represented by the candidates. The law, however, does not forbid single-candidate elections, provided that there are no other candidates nominated. Unified nominations occurred in 49.07% of the villages under survey, and only 1,664 out of 3,267 villages had multiple candidates. For each province, multiple candidates were nominated in 61.06% of Hunan Province, 16.41% of Fujian, and 51.68% of Jilin. The reason for the low rate of multiple candidates was that there was usually only one official candidate left after the primary election. Secret ballots prevailed in all the three provinces, and proxy voting was generally permitted, but not all villages used roving ballot boxes. Fujian had more specific regulations on proxy voting (see Table 7). Table 7: Data on Proxy Voting and Roving Ballot Boxes

Although 84.42% of all the villages allowed proxy voting, and 78.63% of them used roving ballot boxes, the return rate of votes by proxy and roving ballot boxes was rather low, accounting for only 15.15% of the total 2,901,010 ballots collected (see Table 8). The rate was higher in Hunan (24.3%), and lower in Fujian and Jilin, at 4.4% and 7.78% respectively. Table 8: Ballot-casting Methods--Total Data

Table 9: Ballot-casting Methods--by Province

Proxy voting and roving ballot boxes prevailed in some village elections, where it was common for fathers to vote for children and husbands to vote for wives. Although the purpose of proxy voting and roving ballot boxes was to provide convenience for the elderly and the infirm, some villages used these techniques to replace election meetings. Table 10: Secrecy of Ballots (Total Data)

Obviously the transparency of vote counting and on-the-spot announcement of results were also important criteria for good elections, but the survery forms unfortunately lacked relevant questions, so the data cannot reflect these factors. The only indicator of election competition was the percentage of votes received by winning candidates. We assume that a percentage of votes over two thirds indicates a less competitive election than a percentage less than two thirds. Our data indicates that 2,969 of the 3,267 villages successfully elected village chairmen, and of these 2,969 chairmen 1,709 (57.56%) received over two thirds of possible votes, and the other 1,206 (42.44%) reveived less than two thirds of possible votes (see Table 11). Table 11: Degree of Competition per Village

The partial analysis on VC election data illustrates that standardization has been greatly improved, and the percentage of election of non-incumbents has increased. Individual nomination and selection of final candidates according to nomination votes has become the orientation of further development. Cadres of all level have moved towards a consenus favoring secret ballots, multiple candidates, and limitation of proxy voting and roving ballot boxes. Competition, furthermore, has increased. Analysis of Election Results The quality of the elected officials is arguably an important criterion for successful elections. In this regard, the survey included the age, sex and political status of elected VC chairs. We will assume that age indicates something about the cadre’s health, enthusiasm for work, and capability. We generalize that younger cadres would have better health and more energy, enthusiasm and ambition, middle-aged cadres would be more experienced, and cadres over the age of 50 would be less energetic and more conservative. Under these assumptions, cadres under the age of 50 would be preferable. Records indicate that older village cadres predominated in the early reform period. Our data indicates that this trend is changing, with the new average VC chairman age at 44.25. This conclusion corresponds to evidence from the Training Center for Local-level Cadres' 1996 survey (The sample size of the survey is 700, include the chairmen and the committee members. The average age is 40.3, quoted from The Executive Report of the Training Center of the Chinese Local Cadres, pp. 62.) (see Table 12). Table 12: Average Age of Elected VC Chairs

Women still constitute a small percentage of total cadres. Of the 2,969 elected chairs, only 25 were women (0.84%), with a maximum 1.95% rate in Fujian and 0.43% in Jilin (see Table 13). These statistics indicate that, at the very least, women's ability to become elected for VC offices needs to be addressed. The Communist Party still has strong support from the villagers, and 83.50% of the elected chairs are party members (see Table 13), which reveals the image improvement of the party and consolidation of the party authority in dealing with the village affairs. Incumbent reelection most often indicated one of two things. Incumbent leaders had either won the villagers' trust and support through their work, or they had interfered with election procedures illegally. 90.54% of the incumbents in the survey were re-elected, leaving less than 10% of electees as new leaders. We conjecture that most of these re-elections reflect the former situation rather than illegal activity (see Table 13). Table 13: Sex, Political Status and Incumbent Status of Elected VC Chairs

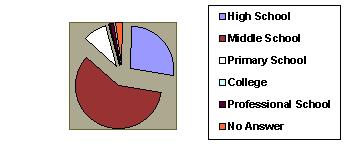

Education levels of officials suggests potential leadership quality as well as knowledge of the science and technology so important for modernization that play an increasingly important role in managing village affairs. The data indicates that most of the elected leaders had completed high school (86.85% in Hunan, 81.71% in Fujian, and 89.57% in Jilin), and another 2.09% of the total had professional degrees (see Table 14). Table 14: Education Levels of VC Chairs

Conclusion Evaluation of village elections has been the most difficult problem in the past ten years of implementation. Unclear references often preclude accurate judgement and blur the focus of work to result in ineffective or problematic policy making. The Carter Center's effort to develop a database improving the collection and assessment of data has proven a valuable experiment in the improvement of understanding actual the realities of village elections. With the above description of the project and the preliminary analysis, we come to the following conclusions:1. There were no major technical obstacles for this project. The rapid development of the data collection program facilitated data storage, transfer and statistical calculation. The extension of the public telephone network greatly reduced the cost of the project. The popularization of computers in the countryside decreased the need for extensive computer literacy training.2. The project was practical. Even though this was the first survey and evaluation project of its kind, all administrative organs involved put in sufficient interest and effort to complete the project. Perhaps the range of the present project could in the future be extended to deal with other aspects of village self-government.3. The data illustrated a significant improvement in the standardization and quality of village elections. Openness and competition have become the major focus of many elections. Less progress has been made regarding controversial procedures such as proxy voting and roving ballot boxes.4. Authority has largely shifted from the older to the younger generation of village leaders. Most of the new leaders are Party members, but this seems to pose no problem. Two key problems that remain are the low percentage of women leaders and the low level of leaders' education, both increasingly crucial for rural development. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||