Guinea worm's scheduled disappearance

Copyright 2005, The National Geographic Society. Posted with permission.

There's no vaccine. There's no cure. You can't develop immunity to the disease caused by this three-foot-long parasite the width of angel-hair pasta.

For millennia - as long as people have waded into lakes and ponds to draw water - Guinea worms have afflicted humans. Today the demise of the worm and the crippling disease it causes may be in sight. But as health workers confront he world's last cases, their jobs are becoming even harder. To eliminate the final holdouts of the disease, health workers must change the behavior of people in some of the poorest, most neglected places on Earth.

The target date for ending Guinea worm disease, once set for 1995, is now 2009. If that date holds, Guinea worm could be he second disease (after smallpox) and the first human parasite to be eradicated in history. The Carter Center, which since 1986 has led the initiatove to stop the scourge, reports that only about 16,000 cases remain, all in Africa.

Guinea worm larvae live in tine crustaceans often referred to as water fleas. When people drink water contaminated by the fleas, their digestive systems destroy the fleas but not the worm larvae, which continue to mature. Male worms die after mating inside their human hosts; females grow ferociously, averaging almost an inch a week. In about a year the worm slowly emerges headfirst, usually from somewhere in the lower legs or arms of the carrier, and caused disabling pain that keeps students from school and farmers from their fields.

The wounds through which the worms come out, inch by excruciating inch, drive suffers to the nearest lake or water source to immerse their sores. When the worms sense the water, they release hundreds of thousands of larvae - and the cycle continues.

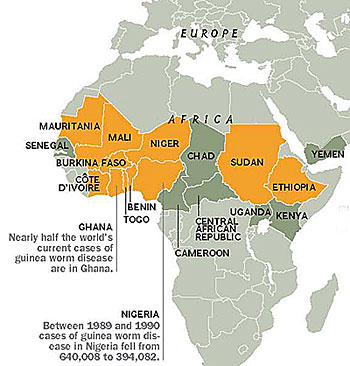

In 1900, Guinea worm was found throughout most of Africa, and the Middle East, and Central and South Asia. As access to safe drinking water spread, the worm disappeared from many regions. Yet by the mid-1980's there were still an estimated 3.5 million cases in Asia and Africa. To get rid of the disease, health workers focused on a simple strategy: Teach people to filter what they drink (even a piece of muslin can do the job) and keep those with emerging worms out of the water. As people passed along these low-tech methods, often from woman to woman, the worms died out. Mali's results are typical: Guinea worm cases plummeted from 10,000 to fewer than 400 in 14 years. But progress was delayed in Sudan and Ghana, which now account for 90 percent of all cases. A 22-year-long civil war that ended earlier this year kept health workers from reaching much of southern Sudan. And eradication efforts in Ghana stalled after ethnic fighting broke out in 1994. To get Ghana's campaign back on track, female health care volunteers stared going house to house in 1002; by early this year reported cased has dropped 60 percent.

Until Guinea worm is completely gone, health workers across Africa will have to remain vigilant-a single infected person could reinfect several villages. "You can't turn your back," says the Carter Center's Aryc Mosher, who is based in Ghana. "The moment you do, it will flare up again."

Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter discusses the Guinea worm project(or search for Challenges for Humanity on www. ngm.com).

Map used with permission of the National Geographic Society.

The Eradication of Guinea worm: afflicted countries.

View full graphic illustration with map (PDF).

Please sign up below for important news about the work of The Carter Center and special event invitations.